A conversation with Mahan Mirarab

Hi, Mahan Mirarab, it is a pleasure to have this delightful conversation with you here in Brussels for Jazz’halo. Thank you very much.

Mahan Mirarab: Thank you, Federico. The pleasure is mine. I'm really happy to have this interview with you, and I am really happy that we could get the chance to see each other in person face to face.

The reason Mahan Mirarab is in Belgium is because he’s playing a concert at Bozar Brussels. Not everybody has the opportunity to play there. He’s considered an artist, a musician who represents a whole generation of young migrant musicians in Europe who actually are changing the sound borders in the music scene and within the music industry. At the same time he’s pushing far away for more diversity with respect for quality, dialogue and creativity. It sounds very similar to his partner Golnar Shahyar.

Can you tell us a little bit about the direction you are taking with your music?

Mahan Mirarab: I was born and grew up in Tehran (Iran), and at 15 I started playing music. I became an established musician in Iran, but I needed more freedom and wanted to explore more in music. In Iran, we had a small community, a jazz community (where we learned everything together), we didn't have any conservatory or even any teacher. We collected our money to make a small conservatory for ourselves and invited a Vahagn Hayrapetian, a teacher from Armenia, who teached us jazz improvisation. He's an wonderful piano player and what he taught us was amazing. It was really more than Jazz, he taught us a lot about music and about humanity, about spirituality. That was a big change for me. What I needed the most was to know more new people and have new experiences in music. That's why I immigrated to Europe in 2009, and in the beginning it was really a big change for me.

I think for every migrant it’s an opportunity to move to a new place, leave home and leave all the family or friends. When you are emigrating, there’s a reason to do it. It's not easy, but when I arrived in Austria I was totally shocked because I expected something really totally different.

In the beginning, I thought that it was interesting that I came from a part of the world, which culture still hasn't been practiced in jazz. I thought it would be interesting for people, but initially that wasn’t the case. I felt that the musicians saw no reasons to play this music because most of the people found that jazz is an American music and it's completely rooted in America. But for me, the question was "OK, but what about Cuban jazz? What about Brazilian jazz? Why are they integrated in jazz or accepted and not when you call like Iranian jazz or whatever?”.

It was a big challenge for me and I started recording an album. I sold my amplifier and that was the only money I had to record an album. I met two beautiful people in Vienna, Robert Jukic, who now lives in Brussels, and Wolfi Rainer, a drummer from Tyrol. We recorded my first album in Vienna. From one side I had this big support from these two guys. From the other side, I saw that this music doesn't really fit in the music industry in Europe. So it was a big challenge. That was the point when I said, "OK, I need some changes. Something is not right here" and I had the privilege to meet Golnar Shahyar in Vienna. As soon as we met, we started collaborating and we are still collaborating together and we are partners now. That was one of the most beautiful gifts that Vienna gave to me.

Everything started with Golnar. She taught me a lot in music and also in how to be active and fight for what you really want. It's still going on, like there is no end to it, but I see a lot of changes. For example microtonal music, when I came to Austria I got really weird comments about micro tonality and people said "This music that you play sounds wrong to my ears". But it's another tuning system. It's not equal temporal temperaments tuning system, which we have in Europe, it is different. And now, this microtonal music is accepted and something hip in music and in contemporary music. A lot of people use it, and now I see that it's interesting for people, also for musicians to listen to microtonal music. The only difference is that when I, as a foreigner, play this microtonal music (which comes from my culture) it is totally different than when a European who starts to learn microtonal music and presents it as contemporary European music, just to let you see that there is a hierarchy in the system. I totally respect the guys who are doing it. I'm a big fan of the people who are really researching in this category, but I see that difference. If I play this music, it is called "World music" and it's totally in a different category, it's not considered as jazz or contemporary music, and that really hurts. But we are trying to change this. I don't want people to call my music “World music” because I think it’s really contemporary music. It's music which comes from my different roots. Iranian culture is not something fixed. There’s a lot of diversity in Iran and its regions. After 13 years living in Europe, I also experienced the culture from Vienna and other cities. I also was in Berlin for two years. A lot of things changed me, and I'm trying to show people that's my identity, and the music that I'm producing is something honest, which is rooted to my identity.

Where and when did you learn to play guitar? Besides guitar, do you play another instrument? I've seen you in concerts, in videos playing other string instruments. Which one came first? The guitar or, I don't even know the names for these traditional instruments or Middle Eastern instruments.

Mahan Mirarab: In the very beginning, the guitar was the first instrument. But the first guitar that I had was my badminton racket in front of the mirror (laughs), so I was just pretending to play guitar as a kid. I loved this instrument, but my family said “Maybe you should start with piano and later you can decide”.

So I started with piano, and at the same time I went to a traditional course for Tar, it's an Iranian instrument. Later I got a guitar from my family. I was impressed by rock music at that time and 80's rock, especially bands like Bon Jovi, Deep Purple and I started just to play the melodies on the guitar. That was the key: listening and playing, and it developed itself like this. That's why I have a totally other technique when I play the guitar, I don't play with pick or I don't have the finger technique like others. I have developed my own technique by playing a lot. As soon as I discovered jazz, it was like a big change to my life.

I remember, the first jazz album that I listened was "Light as a feather" from "Return to forever", and I got the cassette tape from an old shop who had a collection from before the revolution in Iran, in Tehran. I asked him “Can I have something jazz?” I didn't know what jazz means. I just heard the word. The guy gave me the tape and I fell in love with that. I started again, just listening and transcribing. Then I knew other friends who were also obsessed with jazz, and we found the screw and with the screwdriver we could make it loose. We could bring the tempo down, so we could transcribe jazz solos with the tapes, but in a different pitch. That was a big challenge, but it was beautiful. These cassette tapes were my teachers. We found cassette tapes from Bud Powell, I remember, and we played everything from that cassette and later we found a guy also in Tehran who had a collection from London. He supported us a lot, he gave us the collection and we could have an approach to the music, to the jazz music in Iran. That was the key. Then Vahagn Hayrapetian, the Armenian jazz piano player and teacher, came to Iran to teach us music theory and also a lot of other things: music philosophy and many more.

So you also played piano...

Mahan Mirarab: A little bit, for a long time I love guitar. I love to play harmonies on the guitar.

You're answering my next question. Do you have a beloved instrument, a favorite instrument? And if so, which one and why?

Mahan Mirarab: I love sounds. I love different textures. I can't say what's my favorite instrument. It changes in different situations. But during the pandemic, I started a new instrument, it's an Iranian Ney. It's a Bamboo flute, which we play with our teeth and tongue. And I took private lessons to learn the instrument. I love it.

Nothing to do with the strings. Waw!

Mahan Mirarab: No, I found that because I play Fretless guitar, and in classical Iranian music the closest instrument to Fretless guitar is Ney, in my opinion. So I can play the ornaments of Ney easier than ornaments which we play by Tar or Oud.

How did you and Golnar start this beautiful adventure you both have as musicians, and also this fascinating adventure as a couple?

Mahan Mirarab: One of the most beautiful gifts that Vienna gave to me, was Golnar. So I arrived to Vienna and through other musicians a lot of people told me: "Do you know this singer? She's also from Iran and she's living here. She's amazing, you should meet each other". And I was lonely in the beginning and the first year I was focusing on this trio with "Persian side of jazz". And then I got sick. I couldn't play guitar for six months properly and I went to hospital and there I thought: "OK, maybe I should do something". So when I was in hospital, I wrote to Golnar: "Hey, I'm Mahan, I've heard about you. Do you want to meet?" I couldn't really play guitar like now because I had some problems with my nerve system. She answered to me, we met and the first time we met there was a connection, I felt it was really strong and I wanted to discover it more and more and more. It took about 12 years. I'm very grateful. Golnar is an amazing person, an amazing musician, amazing composer, multi-instrumentalist and she's one of my biggest inspirations in my life, my personal life and my musical life.

Your own style is based on micro-tonal music and you've been followed, imitated. Now let us talk about this special guitar because I hear the name Mahan Mirarab and I have an image: always your double guitar. This guitar is actually part of your personality and your physical image. Can you explain why you choose to play a double guitar? Where did you get it? Is it specially made for you?

Mahan Mirarab: First of all, since I was a young child I wanted to be a musician. Because I loved pop and rock music which were played at that time, end of 80s. And that's what inspired me. I wanted to play American music and that's why I wanted to play guitar in general, and then I was all the time searching for, I call it like “American-British pop music”.

I also played Iranian traditional instruments, but I had this mentality that “it's not as much worth as the American music”. I had this prejudice about my own culture. So I wanted to be a “Western guy”. I wanted to be an American. And actually, after playing jazz and after knowing Vahagn and some other friends who had this wisdom to talk about the aspects in music, which are more than only music: there’ also your personality, identity, the culture, how to be honest with the music. It changed a lot in me and I was searching for my identity. I searched for the music that I was listening as a child, for example, the lullabies that we hear, they are microtonal melodies, but the music which my grandmother sang for me is quite different from American. It showed me a lot of new things, and it was the beginning of the way to search for my own sound and my identity. To be honest in the music.

So I bought the fretless guitar in Iran, and I started playing the music of different regions in Iran, not just the classical music, because music in Iran is so diverse. When I think about Iranian music, I think about Arabic music from the south of Iran. I think at Khaliji music, Balochi music, Kurdish music, Azeri music, Turkmen music, Lori Music, and they're all so different. There are different languages and they are all in the same country, and I try to learn them. I try to find the people and play with them. And also I try to learn, re-learn classical music from Iran. I always had two guitars. The main concept to have a double neck guitar was to travel easier. It was about the logistic problems. It makes it a lot easier to travel with my guitar.

Is it easy to find such a guitar?

Mahan Mirarab: No. I was so lucky to meet Ekrem Öskarpat, he is luthier in Istanbul, Turkey, and he's specialized in fretless guitars. He built these two instruments for me.

So it's tailored, especially for Mahan Mirarab.

Mahan Mirarab: Yes, but in Turkey, a lot of people play this guitar and other instruments from Ekrem. Erkan Oğur or Cenk Erdogan, two artists, inspired me a lot.

Is it heavy to carry such kind of guitar?

Mahan Mirarab: It's not heavier than carrying two guitars.

How is it to play a concert with this guitar?

Mahan Mirarab: It's totally fine. Actually, I don't stand when I play, I sit and it's fine. It's everything (laughs). No, it's not that heavy.

You cannot play “alla rock and roll”.

Mahan Mirarab: Yeah, no, no. And I don't want to show off with the guitar, so I usually sit on my chair and it's fine.

I have read that one of your aims in the universe of music and especially jazz is to introduce a new narrative through music in regards to Middle Eastern cultures and jazz. What is your inspiration and motivation? Is your strong sense of Iranianness, of what you have mentioned, your identity? You just told me about the lullabies and your grandmother's memories in these songs, as if you are... paying homage, your dues to your roots, to your ancestors.

Mahan Mirarab: I don't really know. I'm coming from a very normal family. We don't have any family tree. I don't know from which race I'm coming. Really, and I don't care. I'm coming from a very normal family, but I'm always searching for my identity because I want to be honest in my life and in my music. If I didn't care about my identity, I wouldn't be really myself when I'm playing music. So that's the most important thing for me, always search for my identity and always see forward to the future and what's happening. And I like that it changes all the time. I like this change. I like to be open to change.

How many years ago you left Iran.?

Mahan Mirarab: In 2009. Thirteen years.

So in these 13 years do you believe it's appearing this sense of identity or was it before, or perhaps it has been grounded since you are in Europe, what do you think?

Mahan Mirarab: I didn't really have this grounded identity in my life. I'm always searching, it was not always clear for me because my family is not like they are not proud of their Iranian Persianity, and they are living their lives. Nobody talked about these issues in my family, so it was always cool to just leave and enjoy life. And for me, still, to be an Iranian doesn't mean anything for me. I think each person has her or his own culture, and it changes all the time also. If you continue living. All of us are changing, and this identity is changing. That's why I'm totally open to it, and maybe I can call myself in some point I'm very Viennese now because Vienna feels like home for me now. It took a long time to have this feeling, but that's my home, I'm getting inspired from the city, from the language, from the accent, from the food. I don't know how to call myself. It's very confusing.

Going back to jazz, when and why did you choose to play jazz?

Mahan Mirarab: I told you in the first question, I think, as soon as I get this cassette tape from "Chick Corea and Return To Forever – Light As A Feather" by chance, I fell in love with this energy. I never felt this energy in music in my life. Later, I discovered the different periods in jazz, even blues, ragtime, bebop... I saw these changes all the time, and it was really interesting to me to see a community because jazz is about a community. It's not a music genre. I don't count jazz as music genre. It's a community which is developing itself all the time. As a community, how fast can you improve and progress yourself? And that was amazing for me. Like also Joe Zawinul, these guys touched me so much in my life. Coltrane, Zawinul, also the new generation like Tarek Yamani, these new young musicians can touch me with their work.

Your speciality, as it is written on your biography is blending the microtonal system with jazz and improvised music. Could you please guide us a little bit to really understand what microtonal music means?

Mahan Mirarab: There are different approaches to microtonal music. For me it was the microtonal system in the area where I grew up. If you have heard Arabic music, Turkish music, Azerbaijani music, Iranian music, Balochi music, and also Indian music, it came basically from the scales which are different from the European scales, which we called Equal tempered scales with 12 tones. You can divide one octave in different equal intervals, like in thirty one or fifteen or 19 intervals, but in Iran the music has scales in which the intervals are not equal. We have micro tones in the middle of the intervals like European music what we play now, we have C and D, in the middle we have C and C sharp and like C sharp in the middle of C and D but sometimes when I play in microtonal system in Iranian music, for example, the C sharp is higher than the C sharp what we have on the piano, piano keys. And also there are different concepts like Pythagorean scales, which are also based on microtonal tunings. Also just intonation tuning, which is based on the harmonic series from each note. There are different approaches to micro tonal music, which is really interesting for me. In the beginning, I started just to play like Iranian, Arabic, Turkish music with fretlees guitar. But now I'm also curious about the other tuning systems, especially, for example, with with a trio that I'm playing, Mash Trio, we try to compose music in other tuning systems, which is not also from Iran or, I don't know, Arabic Maqam systems. And it's really interesting. I love it.

Besides “Persian Side of Jazz Vol. two” recorded in 2019, you have recorded six more albums. You have recorded Sakinah & friends longing...

Mahan Mirarab: Yes, “Derakht” with Golnar, “Kahgel”, “Darlazeh”, Choub”.

And the first volume from “Persian Side of Jazz” your first album recorded in Austria in 2010.

Mahan Mirarab: Yeah, exactly.

Now, going back to your music, you master the crossing of jazz with traditional Iranian music, which as you have explained is vast. It's very different in between regions, but you call it Persian music. As well, you cross music from other regions, as you have mentioned, Kurdish and Azerbajani. What is the motivation behind your fantastic musical talent, Mahan? What is the connection between these different types of music and jazz?

Mahan Mirarab: Actually, the main concept of jazz for me, the philosophy of jazz is to include everything. Jazz is an inclusive type of music for me. If you see inside jazz, how people musicians got inspired by Cuban musicians, different countries from South America, also African music, sorry that I call it African music because in Africa in each country, each region there is a lot of different music. But how this inspiration actually is the base of jazz. You know this pentatonic scales, which shaped blues in the beginning. And also if you see like the modern jazz, what we have now. And the impact, what John Coltrane brought to it. He got inspired a lot by Korean music. And nobody talks about it. This technique like circular breathing. And if you are talking about spirituality, which came to jazz after people like John Coltrane or Wayne Shorter, I think it's always good to mention that jazz is not just American now. I don't call it American music anymore. It's founded in America. I accept, but it changed the roots. Its roots are now from different parts in the world. It's not just in America. And now you see, again, people like Tigran Hamasyan and how they bring Armenian culture into the jazz or in far East like the Japanese musicians, young musicians. How can they always progress this movement? It's amazing, and it's good to consider it. And unfortunately, these guys have less opportunities in the music industry. If you see the bands, the festivals, maybe you see some exceptions who are not American or European musicians playing in festivals, but it's not enough. It's not diverse at all in the music industry, in the jazz industry. We need this diversity, otherwise it doesn't survive. It can't continue like this. Also, the audience are going less and less and you feel this lack of diversity in Jazz's industry, actually.

Going back to your music. What inspires your music?

Mahan Mirarab: Mostly people. I wrote a lot of songs about my friends, my family and the people that I meet because I didn't force myself to learn Kurdish music or Cuban music. I just wanted to be open to get to know new people. And by chance I had this privilege to play with people like Pavel Urkiza and his amazing Cuban ensemble, which was like a university for me, University of Cuban Music playing with this band or with Sakina, as a Kurdish musician or with the guys from the Orwa Zaleh Ensemble who are really amazing musicians, For me they're playing contemporary music from Syria, and I learned a lot from each of them, and I try to bring them into my culture. I want to expand my culture with all these beautiful things that I experience in my life thanks to these people. So the people are the main reason for me to make music.

How, as a musician, as a composer, have you experienced this situation we live in for the last 20 months, the Corona pandemics?

Mahan Mirarab: Actually, in the beginning it was totally a shock because I had to cancel my CD released tour, a lot of concerts got cancelled and I was totally in shock.

But after a while, I tried to calm down and everything was OK. I have to mention that in Austria, we the musicians, freelance musicians in Austria we had this privilege to have an income during these 20 months, which a lot of musicians in other parts of the world didn't have. In Iran or in Turkey they had nothing. They couldn't really survive because they are full time musicians, so they had to do other jobs.

I really appreciate this privilege that we had in Austria, and we had really time to sit down, spend time at home and relax. Finally relax, because working as a musician is not relaxing at all. To be fit as a musician, I need to practice every day. I have to learn new programs that I'm playing the next month, I have to rehearse with the bands. It's a lot of unpaid responsibilities that we have in our career. We just get paid for a gig, which is still is not enough. So it needs to change. During these 20 months in Austria, a lot of people start to reflect and start to fight against the existing system. For example, the musicians in Austria started to make the prices for their career to put value and for our rehearsals, for concerts and the minimum rate that we need to get paid for each concert. It wasn't fair enough.

A lot of good things happened during the pandemic for me. Now I'm back to my routine. I'm touring again, I'm playing concerts, but now I'm doing this with an awareness because I had this time, this precious time to sit down, reflect and live as a human not all the time running, running, playing, playing all the gigs that I can. And at the end, “I can't stay young forever”, I'm getting older, too (laughs). So it was a great time for me to know myself and make new borders for me in my career.

That's basically the result. And now, since this so-called Corona Pass, in Italy they call it Green Pass. Here in Belgium, they call it CST... things are getting relaxed.

Mahan Mirarab: Opening up.

Yeah, yeah, there are concerts and you’re a proof of it, and I'm sure is going to be packed.

Mahan Mirarab: It's great and I'm really happy because I'm living here for 13 years in Europe and I've never played in Brussels. This month and next month, I'm playing three concerts in Brussels, which is amazing. Next month I'm playing with Bas Majarb in Brussels, and with Golnar and Mahan Trio we play at the Zindering Festival in Mechelen on the 13th of December.

What are your plans for 2022? Do you have concerts, tours and maybe even new projects, new formations, recordings, a new album?

Mahan Mirarab: Yes, I recorded my newest album one month ago in Vienna with the same constellation, but I added a great violin player, Florian V. Leitner, and recorded the compositions that I wrote during the pandemic. It was beautiful to spend time with these people in the studio. We had Monia Matbou Riahi clarinet, Golnar Shahyar voice, Amir Wahba percussion, Martin Berauer bass, Florian Willeitner violin and David Six piano. I think it's my favorite recording (laughs). I'm very excited about it, and I hope that in 2022 and 2023 we will play this program live. But now I'm in this phase of mixing, mastering and publishing the program. Also with Golnar we have a lot of new material and we should record. But now I'm playing mostly with other projects.

I play with Mash trio. We have a lot of concerts for both this and next year. I play in a guitar trio now, Julie Island Guitar Trio. We are three guitar players based in Vienna: Andi Tausch, Martin Bayer and myself. We made a new program and I hope for next year we will play these programs.

Through the years you have been collaborating with many musicians in Austria. You have lived in Austria since 13 years ago. In between you also lived in Berlin. So you are familiar with this German jazz atmosphere. But specifically, as you live, you play and you make your music there in Austria, what will be your opinion, your observations about the jazz made in Austria, let's say the Austrian jazz? How do you see the Austrian Jazz Panorama at the moment?

Mahan Mirarab: It's a good question, because I am very critical for the Austrian jazz scene as much as I really appreciate it, and as much as I appreciate the creative projects which are happening there and the open people who are working in this music scene. What I really miss in Austria is, again, the lack of diversity in jazz. I think the Austrian music scene, is not inclusive enough and I hope that the people in Austria, the musicians in Austria will open up and include more people from other cultural backgrounds to the Austrian music scene and give more space to them and include them in their programs. Also I always criticize the ensembles, especially the funded ensembles, which are most of the time hundred percent white musicians and you don't see a single musician from other countries or even single musicians who look different. I think we need big changes in this scene, and I also want to say that, for example, one of the big changes that happened in Austria - and it's very positive - was Jazz Werkstatt Wien this year, which they changed everything from the curating level up to the program level, like you see the diversity in the curating team and also in the program. And it was an amazing thing what happened this year in Jazz Werkstatt Wien, I've never applied to play in Jazz Werkstatt Wien, because I thought that I had no chance. I have no place because, if you don't see people to include the people from the other communities, although I don't really like this word “other” because it separates the people. But I have to say you don't really try to do because you see no chance. But now they have approached me, and I was really happy to see this change in the music scene in Vienna, and that's what gave me hope for the future. At the same time, I really appreciate the movements in Austria, like in MICA (Music Austria), people like Helge Hinteregger in the scene that are pushing it. Also, “Porgy & Bess”, Christoph Huber, these people are giving space to musicians who are not originally European, and I hope that this diversity will come to jazz scene in Austria.

Do you feel there's more space for musicians like in your case, in Golnar's case, making great jazz like you both do, are they being integrated more and more in the in the Austrian jazz arena or still it remains a little bit like...to be seen?

Mahan Mirarab: Foreigners... (laughs) Yeah. I hope so. There are lots of students, for example, in the university or in conservatories who are foreigners, “foreigner musicians” I call them, I'm allowed to call ourselves foreigners. And if you see, big bands are the place. Big bands can make a lot of changes in the jazz scene. If you include people in big bands, you can show a lot. You see, as soon as big bands start including women in their ensembles, a lot of things changed. Also in the industry. So the people see that, “OK, the quality is not about race or the cultural background. The quality doesn't come from race”, It's crazy to think about it, to think like this in my opinion, and I see the lack of diversity in big bands. Most of the big bands are 100 percent “white” in Austria. That's a pity because you have this huge potential of the people to bring, and it's an advantage for both sides. And it's really a pity that they don't use this potential in the scene and they don't really practice it.

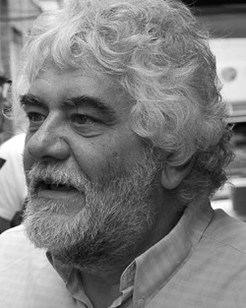

Text © Federico Garcia (Jueves de Jazz) - photos © Saleh Rozati / Georg Cizek Graf

http://radioalma.eu/jazz/author/jazz/

Other

In case you LIKE us, please click here:

Foto © Leentje Arnouts

"WAGON JAZZ"

cycle d’interviews réalisées

par Georges Tonla Briquet

our partners:

Hotel-Brasserie

Markt 2 - 8820 TORHOUT

Silvère Mansis

(10.9.1944 - 22.4.2018)

foto © Dirck Brysse

Rik Bevernage

(19.4.1954 - 6.3.2018)

foto © Stefe Jiroflée

Philippe Schoonbrood

(24.5.1957-30.5.2020)

foto © Dominique Houcmant

Claude Loxhay

(18/02/1947 – 02/11/2023)

foto © Marie Gilon

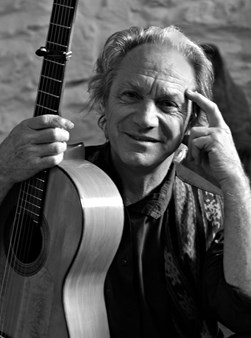

Pedro Soler

(08/06/1938 – 03/08/2024)

foto © Jacky Lepage

Special thanks to our photographers:

Petra Beckers

Ron Beenen

Annie Boedt

Klaas Boelen

Henning Bolte

Serge Braem

Cedric Craps

Luca A. d'Agostino

Christian Deblanc

Philippe De Cleen

Paul De Cloedt

Cindy De Kuyper

Koen Deleu

Ferdinand Dupuis-Panther

Anne Fishburn

Federico Garcia

Jeroen Goddemaer

Robert Hansenne

Serge Heimlich

Dominique Houcmant

Stefe Jiroflée

Herman Klaassen

Philippe Klein

Jos L. Knaepen

Tom Leentjes

Hugo Lefèvre

Jacky Lepage

Olivier Lestoquoit

Eric Malfait

Simas Martinonis

Nina Contini Melis

Anne Panther

France Paquay

Francesca Patella

Quentin Perot

Jean-Jacques Pussiau

Arnold Reyngoudt

Jean Schoubs

Willy Schuyten

Frank Tafuri

Jean-Pierre Tillaert

Tom Vanbesien

Jef Vandebroek

Geert Vandepoele

Guy Van de Poel

Cees van de Ven

Donata van de Ven

Harry van Kesteren

Geert Vanoverschelde

Roger Vantilt

Patrick Van Vlerken

Marie-Anne Ver Eecke

Karine Vergauwen

Frank Verlinden

Jan Vernieuwe

Anders Vranken

Didier Wagner

and to our writers:

Mischa Andriessen

Robin Arends

Marleen Arnouts

Werner Barth

José Bedeur

Henning Bolte

Erik Carrette

Danny De Bock

Denis Desassis

Pierre Dulieu

Ferdinand Dupuis-Panther

Federico Garcia

Paul Godderis

Stephen Godsall

Jean-Pierre Goffin

Claudy Jalet

Chris Joris

Bernard Lefèvre

Mathilde Löffler

Claude Loxhay

Ieva Pakalniškytė

Anne Panther

Etienne Payen

Quentin Perot

Jacques Prouvost

Renato Sclaunich

Yves « JB » Tassin

Herman te Loo

Eric Therer

Georges Tonla Briquet

Henri Vandenberghe

Peter Van De Vijvere

Iwein Van Malderen

Jan Van Stichel

Olivier Verhelst